Extrapolation tips and tricks#

Handling of extrapolation—evaluation of the interpolators on query

points outside of the domain of interpolated data—is not fully

consistent among different routines in scipy.interpolate. Different

interpolators use different sets of keyword arguments to control the behavior

outside of the data domain: some use extrapolate=True/False/None, some

allow the fill_value keyword. Refer to the API documentation for details

for each specific interpolation routine.

Depending on a particular problem, the available keywords may or may not be sufficient. Special attention needs to be paid to extrapolation of non-linear interpolants. Very often the extrapolated results make less sense with increasing distance from the data domain. This is of course to be expected: an interpolant only knows the data within the data domain.

When the default extrapolated results are not adequate, users need to implement the desired extrapolation mode themselves.

In this tutorial, we consider several worked examples where we demonstrate both the use of available keywords and manual implementation of desired extrapolation modes. These examples may or may not be applicable to your particular problem; they are not necessarily best practices; and they are deliberately pared down to bare essentials needed to demonstrate the main ideas, in a hope that they serve as an inspiration for your handling of your particular problem.

interp1d : replicate numpy.interp left and right fill values#

TL;DR: Use fill_value=(left, right)

numpy.interp uses constant extrapolation, and defaults to extending

the first and last values of the y array in the interpolation

interval: the output of np.interp(xnew, x, y) is y[0] for

xnew < x[0] and y[-1] for xnew > x[-1].

By default, interp1d refuses to extrapolate, and raises a

ValueError when evaluated on a data point outside of the

interpolation range. This can be switched off by the

bounds_error=False argument: then interp1d sets the out-of-range

values with the fill_value, which is nan by default.

To mimic the behavior of numpy.interp with interp1d, you can use

the fact that it supports a 2-tuple as the fill_value. The tuple

elements are then used to fill for xnew < min(x) and x > max(x),

respectively. For multidimensional y, these elements must have the

same shape as y or be broadcastable to it.

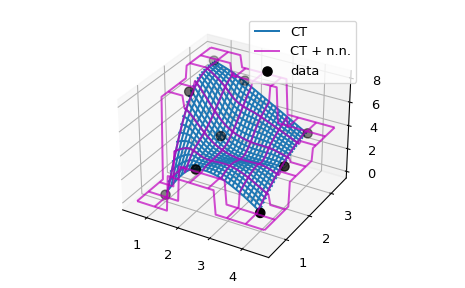

To illustrate:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.interpolate import interp1d

x = np.linspace(0, 1.5*np.pi, 11)

y = np.column_stack((np.cos(x), np.sin(x))) # y.shape is (11, 2)

func = interp1d(x, y,

axis=0, # interpolate along columns

bounds_error=False,

kind='linear',

fill_value=(y[0], y[-1]))

xnew = np.linspace(-np.pi, 2.5*np.pi, 51)

ynew = func(xnew)

fix, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(8, 4))

ax1.plot(xnew, ynew[:, 0])

ax1.plot(x, y[:, 0], 'o')

ax2.plot(xnew, ynew[:, 1])

ax2.plot(x, y[:, 1], 'o')

plt.tight_layout()

CubicSpline extend the boundary conditions#

CubicSpline needs two extra boundary conditions, which are

controlled by the bc_type parameter. This parameter can either list

explicit values of derivatives at the edges, or use helpful aliases. For

instance, bc_type="clamped" sets the first derivatives to zero,

bc_type="natural" sets the second derivatives to zero (two other

recognized string values are “periodic” and “not-a-knot”)

While the extrapolation is controlled by the boundary condition, the

relation is not very intuitive. For instance, one can expect that for

bc_type="natural", the extrapolation is linear. This expectation is

too strong: each boundary condition sets the derivatives at a single

point, at the boundary only. Extrapolation is done from the first and

last polynomial pieces, which — for a natural spline — is a cubic with a

zero second derivative at a given point.

One other way of seeing why this expectation is too strong is to consider a dataset with only three data points, where the spline has two polynomial pieces. To extrapolate linearly, this expectation implies that both of these pieces are linear. But then, two linear pieces cannot match at a middle point with a continuous 2nd derivative! (Unless of course, if all three data points actually lie on a single straight line).

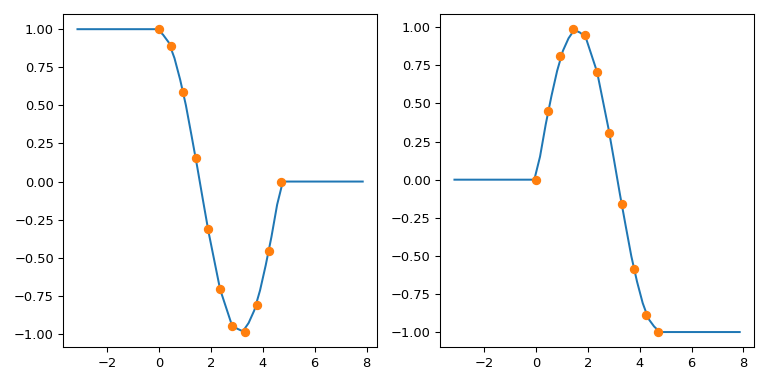

To illustrate the behavior we consider a synthetic dataset and compare several boundary conditions:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.interpolate import CubicSpline

xs = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

ys = [4.5, 3.6, 1.6, 0.0, -3.3, -3.1, -1.8, -1.7]

notaknot = CubicSpline(xs, ys, bc_type='not-a-knot')

natural = CubicSpline(xs, ys, bc_type='natural')

clamped = CubicSpline(xs, ys, bc_type='clamped')

xnew = np.linspace(min(xs) - 4, max(xs) + 4, 101)

splines = [notaknot, natural, clamped]

titles = ['not-a-knot', 'natural', 'clamped']

fig, axs = plt.subplots(3, 3, figsize=(12, 12))

for i in [0, 1, 2]:

for j, spline, title in zip(range(3), splines, titles):

axs[i, j].plot(xs, spline(xs, nu=i),'o')

axs[i, j].plot(xnew, spline(xnew, nu=i),'-')

axs[i, j].set_title(f'{title}, deriv={i}')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

It is clearly seen that the natural spline does have the zero second

derivative at the boundaries, but extrapolation is non-linear.

bc_type="clamped" shows a similar behavior: first derivatives are only

equal to zero exactly at the boundary. In all cases, extrapolation is done by

extending the first and last polynomial pieces of the spline, whatever they

happen to be.

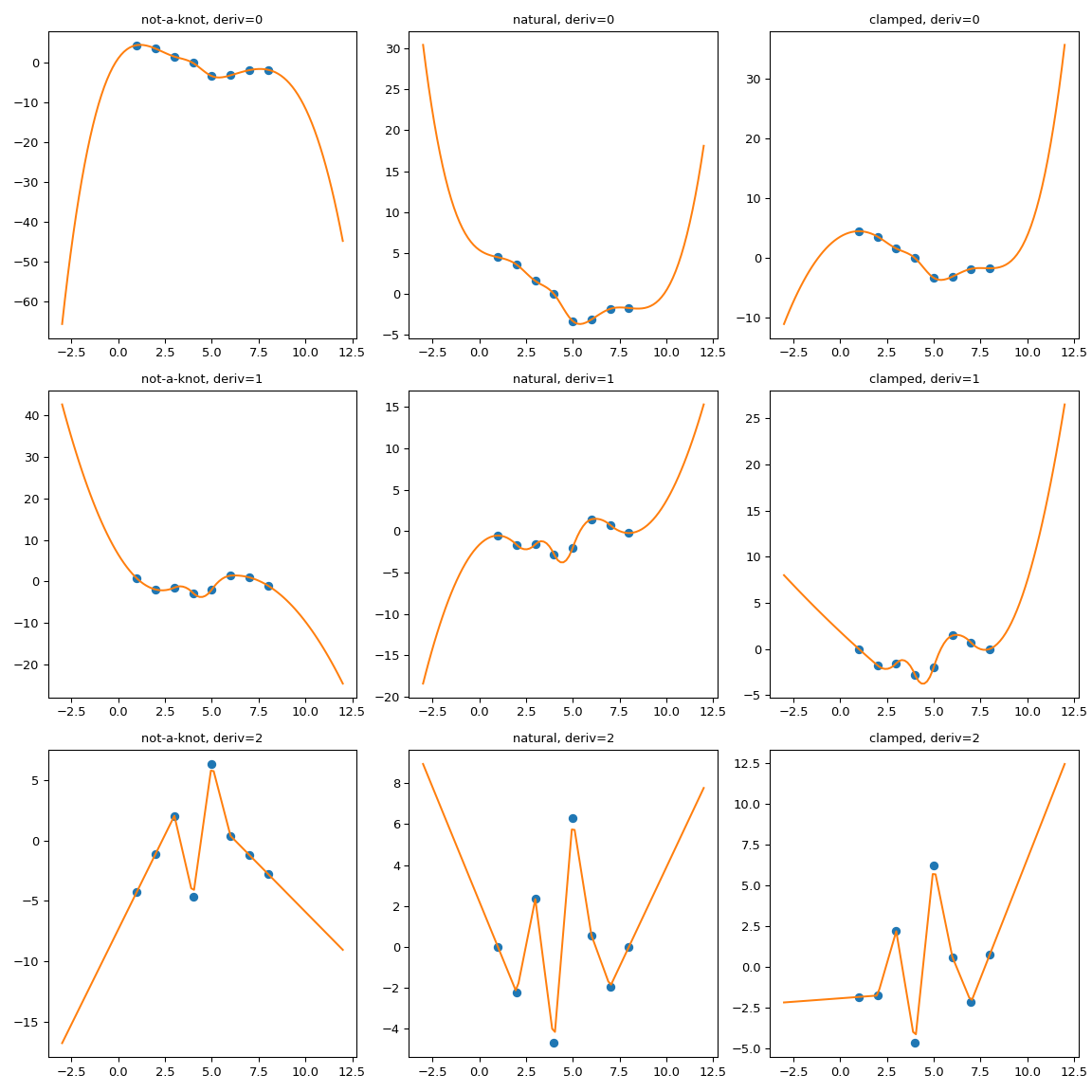

One possible way to force the extrapolation is to extend the interpolation domain to add first and last polynomial pieces which have desired properties.

Here we use extend method of the CubicSpline superclass,

PPoly, to add two extra breakpoints and to make sure that the additional

polynomial pieces maintain the values of the derivatives. Then the

extrapolation proceeds using these two additional intervals.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.interpolate import CubicSpline

def add_boundary_knots(spline):

"""

Add knots infinitesimally to the left and right.

Additional intervals are added to have zero 2nd and 3rd derivatives,

and to maintain the first derivative from whatever boundary condition

was selected. The spline is modified in place.

"""

# determine the slope at the left edge

leftx = spline.x[0]

lefty = spline(leftx)

leftslope = spline(leftx, nu=1)

# add a new breakpoint just to the left and use the

# known slope to construct the PPoly coefficients.

leftxnext = np.nextafter(leftx, leftx - 1)

leftynext = lefty + leftslope*(leftxnext - leftx)

leftcoeffs = np.array([0, 0, leftslope, leftynext])

spline.extend(leftcoeffs[..., None], np.r_[leftxnext])

# repeat with additional knots to the right

rightx = spline.x[-1]

righty = spline(rightx)

rightslope = spline(rightx,nu=1)

rightxnext = np.nextafter(rightx, rightx + 1)

rightynext = righty + rightslope * (rightxnext - rightx)

rightcoeffs = np.array([0, 0, rightslope, rightynext])

spline.extend(rightcoeffs[..., None], np.r_[rightxnext])

xs = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

ys = [4.5, 3.6, 1.6, 0.0, -3.3, -3.1, -1.8, -1.7]

notaknot = CubicSpline(xs,ys, bc_type='not-a-knot')

# not-a-knot does not require additional intervals

natural = CubicSpline(xs,ys, bc_type='natural')

# extend the natural natural spline with linear extrapolating knots

add_boundary_knots(natural)

clamped = CubicSpline(xs,ys, bc_type='clamped')

# extend the clamped spline with constant extrapolating knots

add_boundary_knots(clamped)

xnew = np.linspace(min(xs) - 5, max(xs) + 5, 201)

fig, axs = plt.subplots(3, 3,figsize=(12,12))

splines = [notaknot, natural, clamped]

titles = ['not-a-knot', 'natural', 'clamped']

for i in [0, 1, 2]:

for j, spline, title in zip(range(3), splines, titles):

axs[i, j].plot(xs, spline(xs, nu=i),'o')

axs[i, j].plot(xnew, spline(xnew, nu=i),'-')

axs[i, j].set_title(f'{title}, deriv={i}')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Manually implement the asymptotics#

The previous trick of extending the interpolation domain relies on the

CubicSpline.extend method. A somewhat more general alternative is to

implement a wrapper which handles the out-of-bounds behavior explicitly.

Let us consider a worked example.

The setup#

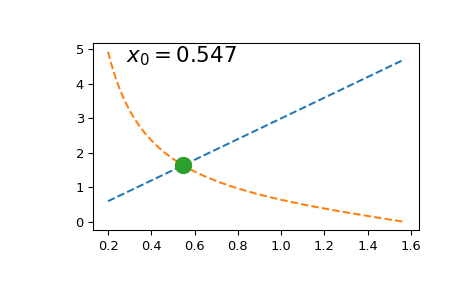

Suppose we want to solve at a given value of \(a\) the equation

(One application where these kinds of equations appear is solving for energy levels of a quantum particle). For simplicity, let’s only consider \(x\in (0, \pi/2)\).

Solving this equation once is straightforward:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.optimize import brentq

def f(x, a):

return a*x - 1/np.tan(x)

a = 3

x0 = brentq(f, 1e-16, np.pi/2, args=(a,)) # here we shift the left edge

# by a machine epsilon to avoid

# a division by zero at x=0

xx = np.linspace(0.2, np.pi/2, 101)

plt.plot(xx, a*xx, '--')

plt.plot(xx, 1/np.tan(xx), '--')

plt.plot(x0, a*x0, 'o', ms=12)

plt.text(0.1, 0.9, fr'$x_0 = {x0:.3f}$',

transform=plt.gca().transAxes, fontsize=16)

plt.show()

However, if we need to solve it multiple times (e.g. to find a series

of roots due to periodicity of the tan function), repeated calls to

scipy.optimize.brentq become prohibitively expensive.

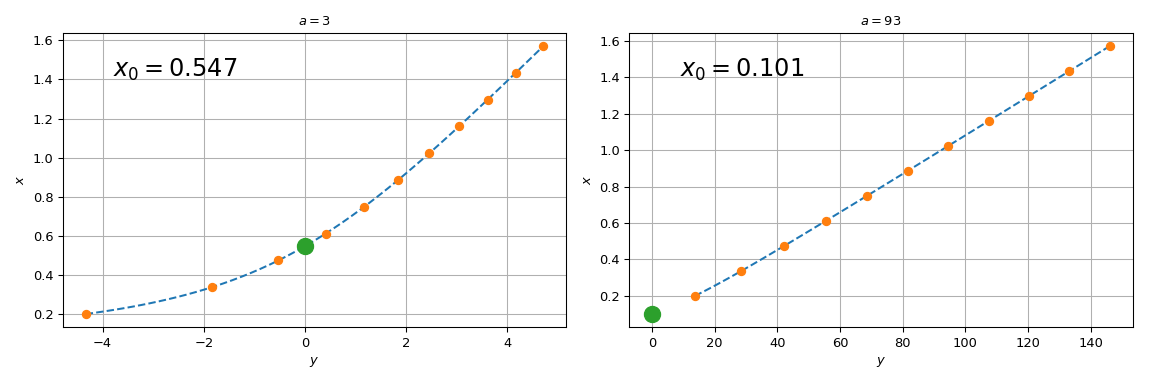

To circumvent this difficulty, we tabulate \(y = ax - 1/\tan{x}\) and interpolate it on the tabulated grid. In fact, we will use the inverse interpolation: we interpolate the values of \(x\) versus \(у\). This way, solving the original equation becomes simply an evaluation of the interpolated function at zero \(y\) argument.

To improve the interpolation accuracy we will use the knowledge of the

derivatives of the tabulated function. We will use

BPoly.from_derivatives to construct a cubic interpolant

(equivalently, we could have used CubicHermiteSpline)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.interpolate import BPoly

def f(x, a):

return a*x - 1/np.tan(x)

xleft, xright = 0.2, np.pi/2

x = np.linspace(xleft, xright, 11)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 4))

for j, a in enumerate([3, 93]):

y = f(x, a)

dydx = a + 1./np.sin(x)**2 # d(ax - 1/tan(x)) / dx

dxdy = 1 / dydx # dx/dy = 1 / (dy/dx)

xdx = np.c_[x, dxdy]

spl = BPoly.from_derivatives(y, xdx) # inverse interpolation

yy = np.linspace(f(xleft, a), f(xright, a), 51)

ax[j].plot(yy, spl(yy), '--')

ax[j].plot(y, x, 'o')

ax[j].set_xlabel(r'$y$')

ax[j].set_ylabel(r'$x$')

ax[j].set_title(rf'$a = {a}$')

ax[j].plot(0, spl(0), 'o', ms=12)

ax[j].text(0.1, 0.85, fr'$x_0 = {spl(0):.3f}$',

transform=ax[j].transAxes, fontsize=18)

ax[j].grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Note that for \(a=3\), spl(0) agrees with the brentq call

above, while for \(a = 93\), the difference is substantial. The

reason the procedure starts failing for large \(a\) is that the

straight line \(y = ax\) tends towards the vertical axis, and the

root of the original equation tends towards \(x=0\). Since we

tabulated the original function at a finite grid, spl(0) involves

extrapolation for too-large values of \(a\). Relying on

extrapolation is prone to losing accuracy and is best avoided.

Use the known asymptotics#

Looking at the original equation, we note that for \(x\to 0\), \(\tan(x) = x + O(x^3)\), and the original equation becomes

so that \(x_0 \approx 1/\sqrt{a}\) for \(a \gg 1\).

We will use this to cook up a class which switches from interpolation to using this known asymptotic behavior for out-of-range data. A bare-bones implementation may look like this

class RootWithAsymptotics:

def __init__(self, a):

# construct the interpolant

xleft, xright = 0.2, np.pi/2

x = np.linspace(xleft, xright, 11)

y = f(x, a)

dydx = a + 1./np.sin(x)**2 # d(ax - 1/tan(x)) / dx

dxdy = 1 / dydx # dx/dy = 1 / (dy/dx)

# inverse interpolation

self.spl = BPoly.from_derivatives(y, np.c_[x, dxdy])

self.a = a

def root(self):

out = self.spl(0)

asympt = 1./np.sqrt(self.a)

return np.where(spl.x.min() < asympt, out, asympt)

And then

>>> r = RootWithAsymptotics(93)

>>> r.root()

array(0.10369517)

which differs from the extrapolated result and agrees with the brentq call.

Note that this implementation is intentionally pared down. From the API

perspective, you may want to instead implement the __call__ method

so that the full dependence of x on y is available. From the

numerical perspective, more work is needed to make sure that the switch

between interpolation and asymptotics occurs deep enough into the

asymptotic regime, so that the resulting function is smooth enough at

the switch-over point.

Also in this example we artificially limited the problem to only

consider a single periodicity interval of the tan function, and only

dealt with \(a > 0\). For negative values of \(a\), we would need

to implement the other asymptotics, for \(x\to \pi\).

However the basic idea is the same.

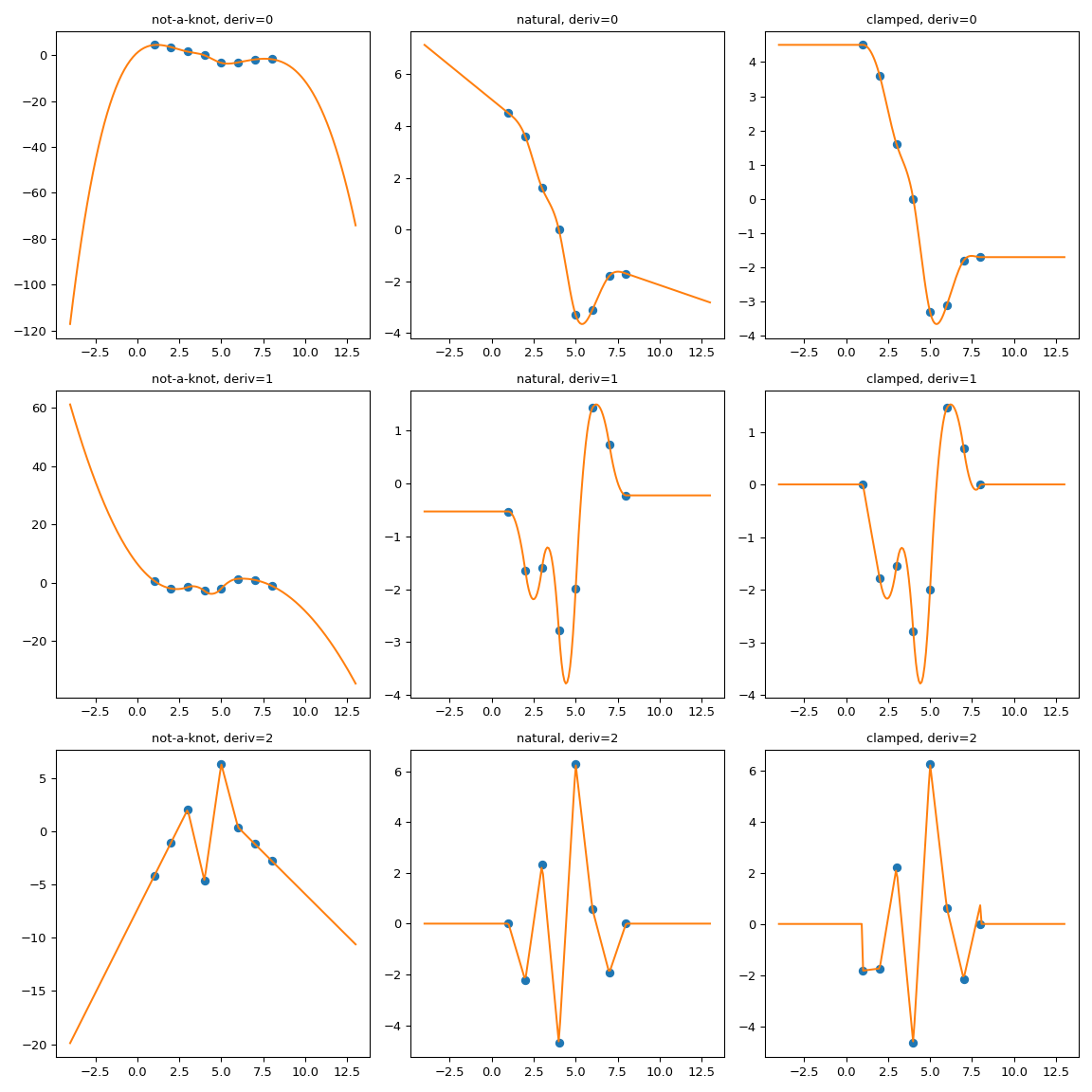

Exrapolation in D > 1#

The basic idea of implementing extrapolation manually in a wrapper class

or function can be easily generalized to higher dimensions. As an

example, we consider a C1-smooth interpolation problem of 2D data using

CloughTocher2DInterpolator. By default, it fills the out of bounds values

with nans, and we want to instead use for each query

point the value of its nearest neighbor.

Since CloughTocher2DInterpolator accepts either 2D data or a Delaunay

triangulation of the data points, the efficient way of finding nearest

neighbors of query points would be to construct the triangulation (using

scipy.spatial tools) and use it to find nearest neighbors on the convex hull

of the data.

We will instead use a simpler, naive method and rely on looping over the whole dataset using NumPy broadcasting.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.interpolate import CloughTocher2DInterpolator as CT

def my_CT(xy, z):

"""CT interpolator + nearest-neighbor extrapolation.

Parameters

----------

xy : ndarray, shape (npoints, ndim)

Coordinates of data points

z : ndarray, shape (npoints)

Values at data points

Returns

-------

func : callable

A callable object which mirrors the CT behavior,

with an additional neareast-neighbor extrapolation

outside of the data range.

"""

x = xy[:, 0]

y = xy[:, 1]

f = CT(xy, z)

# this inner function will be returned to a user

def new_f(xx, yy):

# evaluate the CT interpolator. Out-of-bounds values are nan.

zz = f(xx, yy)

nans = np.isnan(zz)

if nans.any():

# for each nan point, find its nearest neighbor

inds = np.argmin(

(x[:, None] - xx[nans])**2 +

(y[:, None] - yy[nans])**2

, axis=0)

# ... and use its value

zz[nans] = z[inds]

return zz

return new_f

# Now illustrate the difference between the original ``CT`` interpolant

# and ``my_CT`` on a small example:

x = np.array([1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 4, 4, 4])

y = np.array([1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3])

z = np.array([0, 7, 8, 3, 4, 7, 1, 3, 4])

xy = np.c_[x, y]

lut = CT(xy, z)

lut2 = my_CT(xy, z)

X = np.linspace(min(x) - 0.5, max(x) + 0.5, 71)

Y = np.linspace(min(y) - 0.5, max(y) + 0.5, 71)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(X, Y)

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(projection='3d')

ax.plot_wireframe(X, Y, lut(X, Y), label='CT')

ax.plot_wireframe(X, Y, lut2(X, Y), color='m',

cstride=10, rstride=10, alpha=0.7, label='CT + n.n.')

ax.scatter(x, y, z, 'o', color='k', s=48, label='data')

ax.legend()

plt.tight_layout()