Optimization (scipy.optimize)¶

The scipy.optimize package provides several commonly used optimization algorithms. An detailed listing is available: scipy.optimize (can also be found by help(scipy.optimize)).

The module contains:

- Unconstrained and constrained minimization and least-squares algorithms (e.g., fmin: Nelder-Mead simplex, fmin_bfgs: BFGS, fmin_ncg: Newton Conjugate Gradient, leastsq: Levenberg-Marquardt, fmin_cobyla: COBYLA).

- Global (brute-force) optimization routines (e.g., anneal)

- Curve fitting (curve_fit)

- Scalar function minimizers and root finders (e.g., Brent’s method fminbound, and newton)

- Multivariate equation system solvers (fsolve)

- Large-scale multivariate equation system solvers (e.g. newton_krylov)

Below, several examples demonstrate their basic usage.

Nelder-Mead Simplex algorithm (fmin)¶

The simplex algorithm is probably the simplest way to minimize a

fairly well-behaved function. The simplex algorithm requires only

function evaluations and is a good choice for simple minimization

problems. However, because it does not use any gradient evaluations,

it may take longer to find the minimum. To demonstrate the

minimization function consider the problem of minimizing the

Rosenbrock function of  variables:

variables:

![\[ f\left(\mathbf{x}\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{N-1}100\left(x_{i}-x_{i-1}^{2}\right)^{2}+\left(1-x_{i-1}\right)^{2}.\]](../_images/math/2cd91295e06479e61445b54e23852a2e50b14e3c.png)

The minimum value of this function is 0 which is achieved when  This minimum can be found using the fmin routine as shown in the example below:

This minimum can be found using the fmin routine as shown in the example below:

>>> from scipy.optimize import fmin

>>> def rosen(x):

... """The Rosenbrock function"""

... return sum(100.0*(x[1:]-x[:-1]**2.0)**2.0 + (1-x[:-1])**2.0)

>>> x0 = [1.3, 0.7, 0.8, 1.9, 1.2]

>>> xopt = fmin(rosen, x0, xtol=1e-8)

Optimization terminated successfully.

Current function value: 0.000000

Iterations: 339

Function evaluations: 571

>>> print xopt

[ 1. 1. 1. 1. 1.]

Another optimization algorithm that needs only function calls to find the minimum is Powell’s method available as fmin_powell.

Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno algorithm (fmin_bfgs)¶

In order to converge more quickly to the solution, this routine uses the gradient of the objective function. If the gradient is not given by the user, then it is estimated using first-differences. The Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) method typically requires fewer function calls than the simplex algorithm even when the gradient must be estimated.

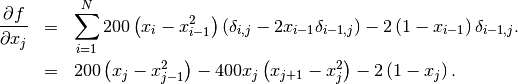

To demonstrate this algorithm, the Rosenbrock function is again used. The gradient of the Rosenbrock function is the vector:

This expression is valid for the interior derivatives. Special cases are

A Python function which computes this gradient is constructed by the code-segment:

>>> def rosen_der(x):

... xm = x[1:-1]

... xm_m1 = x[:-2]

... xm_p1 = x[2:]

... der = zeros_like(x)

... der[1:-1] = 200*(xm-xm_m1**2) - 400*(xm_p1 - xm**2)*xm - 2*(1-xm)

... der[0] = -400*x[0]*(x[1]-x[0]**2) - 2*(1-x[0])

... der[-1] = 200*(x[-1]-x[-2]**2)

... return der

The calling signature for the BFGS minimization algorithm is similar to fmin with the addition of the fprime argument. An example usage of fmin_bfgs is shown in the following example which minimizes the Rosenbrock function.

>>> from scipy.optimize import fmin_bfgs

>>> x0 = [1.3, 0.7, 0.8, 1.9, 1.2]

>>> xopt = fmin_bfgs(rosen, x0, fprime=rosen_der)

Optimization terminated successfully.

Current function value: 0.000000

Iterations: 53

Function evaluations: 65

Gradient evaluations: 65

>>> print xopt

[ 1. 1. 1. 1. 1.]

Newton-Conjugate-Gradient (fmin_ncg)¶

The method which requires the fewest function calls and is therefore often the fastest method to minimize functions of many variables is fmin_ncg. This method is a modified Newton’s method and uses a conjugate gradient algorithm to (approximately) invert the local Hessian. Newton’s method is based on fitting the function locally to a quadratic form:

![\[ f\left(\mathbf{x}\right)\approx f\left(\mathbf{x}_{0}\right)+\nabla f\left(\mathbf{x}_{0}\right)\cdot\left(\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{x}_{0}\right)+\frac{1}{2}\left(\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{x}_{0}\right)^{T}\mathbf{H}\left(\mathbf{x}_{0}\right)\left(\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{x}_{0}\right).\]](../_images/math/f0534e9ffda6595b8a080dd62dc91952c41ff681.png)

where  is a matrix of second-derivatives (the Hessian). If the Hessian is

positive definite then the local minimum of this function can be found

by setting the gradient of the quadratic form to zero, resulting in

is a matrix of second-derivatives (the Hessian). If the Hessian is

positive definite then the local minimum of this function can be found

by setting the gradient of the quadratic form to zero, resulting in

![\[ \mathbf{x}_{\textrm{opt}}=\mathbf{x}_{0}-\mathbf{H}^{-1}\nabla f.\]](../_images/math/749539f9cd9c8fa6ee61e67cff898b54f3077a5e.png)

The inverse of the Hessian is evaluted using the conjugate-gradient method. An example of employing this method to minimizing the Rosenbrock function is given below. To take full advantage of the NewtonCG method, a function which computes the Hessian must be provided. The Hessian matrix itself does not need to be constructed, only a vector which is the product of the Hessian with an arbitrary vector needs to be available to the minimization routine. As a result, the user can provide either a function to compute the Hessian matrix, or a function to compute the product of the Hessian with an arbitrary vector.

Full Hessian example:¶

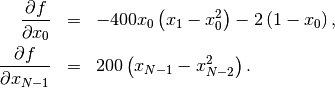

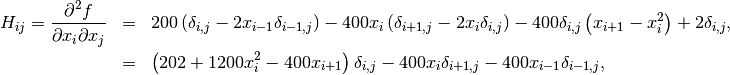

The Hessian of the Rosenbrock function is

if ![i,j\in\left[1,N-2\right]](../_images/math/a42ca4fb62cec850a850efeec2effe6f60244af0.png) with

with ![i,j\in\left[0,N-1\right]](../_images/math/b0c94de6425aea4ecd9ceb9bea133f399367b9b9.png) defining the

defining the  matrix. Other non-zero entries of the matrix are

matrix. Other non-zero entries of the matrix are

For example, the Hessian when  is

is

![\[ \mathbf{H}=\left[\begin{array}{ccccc} 1200x_{0}^{2}-400x_{1}+2 & -400x_{0} & 0 & 0 & 0\\ -400x_{0} & 202+1200x_{1}^{2}-400x_{2} & -400x_{1} & 0 & 0\\ 0 & -400x_{1} & 202+1200x_{2}^{2}-400x_{3} & -400x_{2} & 0\\ 0 & & -400x_{2} & 202+1200x_{3}^{2}-400x_{4} & -400x_{3}\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -400x_{3} & 200\end{array}\right].\]](../_images/math/1ca36bb25b64ff242a87c1bc7469fabdbad74271.png)

The code which computes this Hessian along with the code to minimize the function using fmin_ncg is shown in the following example:

>>> from scipy.optimize import fmin_ncg

>>> def rosen_hess(x):

... x = asarray(x)

... H = diag(-400*x[:-1],1) - diag(400*x[:-1],-1)

... diagonal = zeros_like(x)

... diagonal[0] = 1200*x[0]-400*x[1]+2

... diagonal[-1] = 200

... diagonal[1:-1] = 202 + 1200*x[1:-1]**2 - 400*x[2:]

... H = H + diag(diagonal)

... return H

>>> x0 = [1.3, 0.7, 0.8, 1.9, 1.2]

>>> xopt = fmin_ncg(rosen, x0, rosen_der, fhess=rosen_hess, avextol=1e-8)

Optimization terminated successfully.

Current function value: 0.000000

Iterations: 23

Function evaluations: 26

Gradient evaluations: 23

Hessian evaluations: 23

>>> print xopt

[ 1. 1. 1. 1. 1.]

Hessian product example:¶

For larger minimization problems, storing the entire Hessian matrix can consume considerable time and memory. The Newton-CG algorithm only needs the product of the Hessian times an arbitrary vector. As a result, the user can supply code to compute this product rather than the full Hessian by setting the fhess_p keyword to the desired function. The fhess_p function should take the minimization vector as the first argument and the arbitrary vector as the second argument. Any extra arguments passed to the function to be minimized will also be passed to this function. If possible, using Newton-CG with the hessian product option is probably the fastest way to minimize the function.

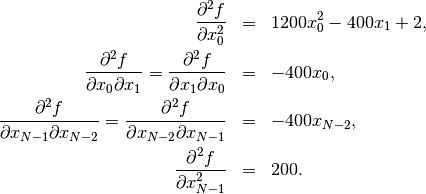

In this case, the product of the Rosenbrock Hessian with an arbitrary

vector is not difficult to compute. If  is the arbitrary vector, then

is the arbitrary vector, then  has elements:

has elements:

![\[ \mathbf{H}\left(\mathbf{x}\right)\mathbf{p}=\left[\begin{array}{c} \left(1200x_{0}^{2}-400x_{1}+2\right)p_{0}-400x_{0}p_{1}\\ \vdots\\ -400x_{i-1}p_{i-1}+\left(202+1200x_{i}^{2}-400x_{i+1}\right)p_{i}-400x_{i}p_{i+1}\\ \vdots\\ -400x_{N-2}p_{N-2}+200p_{N-1}\end{array}\right].\]](../_images/math/6c4675fa762e45e8c7b9a55255c3e520ea5d0477.png)

Code which makes use of the fhess_p keyword to minimize the Rosenbrock function using fmin_ncg follows:

>>> from scipy.optimize import fmin_ncg

>>> def rosen_hess_p(x,p):

... x = asarray(x)

... Hp = zeros_like(x)

... Hp[0] = (1200*x[0]**2 - 400*x[1] + 2)*p[0] - 400*x[0]*p[1]

... Hp[1:-1] = -400*x[:-2]*p[:-2]+(202+1200*x[1:-1]**2-400*x[2:])*p[1:-1] \

... -400*x[1:-1]*p[2:]

... Hp[-1] = -400*x[-2]*p[-2] + 200*p[-1]

... return Hp

>>> x0 = [1.3, 0.7, 0.8, 1.9, 1.2]

>>> xopt = fmin_ncg(rosen, x0, rosen_der, fhess_p=rosen_hess_p, avextol=1e-8)

Optimization terminated successfully.

Current function value: 0.000000

Iterations: 22

Function evaluations: 25

Gradient evaluations: 22

Hessian evaluations: 54

>>> print xopt

[ 1. 1. 1. 1. 1.]

Least-square fitting (leastsq)¶

All of the previously-explained minimization procedures can be used to

solve a least-squares problem provided the appropriate objective

function is constructed. For example, suppose it is desired to fit a

set of data  to a known model,

to a known model,

where

where  is a vector of parameters for the model that

need to be found. A common method for determining which parameter

vector gives the best fit to the data is to minimize the sum of squares

of the residuals. The residual is usually defined for each observed

data-point as

is a vector of parameters for the model that

need to be found. A common method for determining which parameter

vector gives the best fit to the data is to minimize the sum of squares

of the residuals. The residual is usually defined for each observed

data-point as

![\[ e_{i}\left(\mathbf{p},\mathbf{y}_{i},\mathbf{x}_{i}\right)=\left\Vert \mathbf{y}_{i}-\mathbf{f}\left(\mathbf{x}_{i},\mathbf{p}\right)\right\Vert .\]](../_images/math/eb3564391ae7831326315a47605a9af7f5e84ba6.png)

An objective function to pass to any of the previous minization algorithms to obtain a least-squares fit is.

![\[ J\left(\mathbf{p}\right)=\sum_{i=0}^{N-1}e_{i}^{2}\left(\mathbf{p}\right).\]](../_images/math/e5d19e9d6d1b9a59962a43d0a22b9a43f45c3b22.png)

The leastsq algorithm performs this squaring and summing of the

residuals automatically. It takes as an input argument the vector

function  and returns the

value of

and returns the

value of  which minimizes

which minimizes

directly. The user is also encouraged to provide the Jacobian matrix

of the function (with derivatives down the columns or across the

rows). If the Jacobian is not provided, it is estimated.

directly. The user is also encouraged to provide the Jacobian matrix

of the function (with derivatives down the columns or across the

rows). If the Jacobian is not provided, it is estimated.

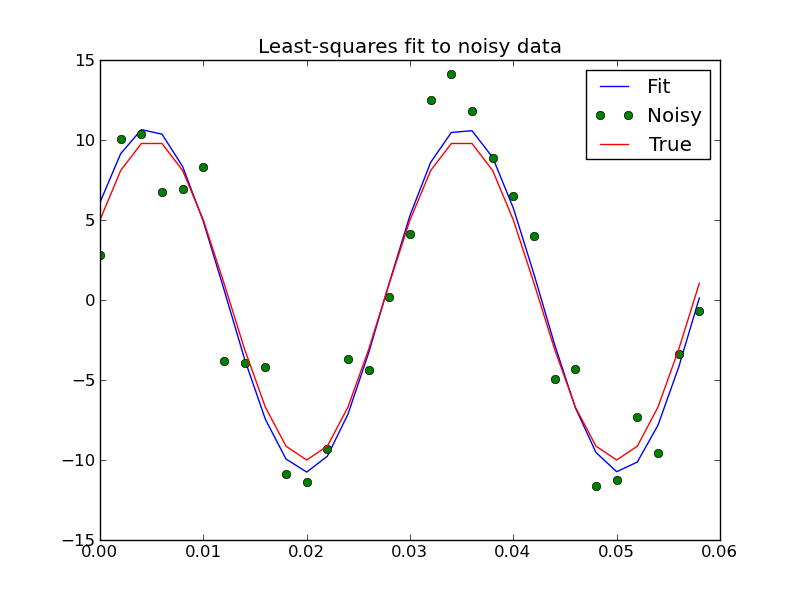

An example should clarify the usage. Suppose it is believed some measured data follow a sinusoidal pattern

![\[ y_{i}=A\sin\left(2\pi kx_{i}+\theta\right)\]](../_images/math/b40b588f31a90a9d06f7e32624641c5d648e4bb9.png)

where the parameters

, and

, and  are unknown. The residual vector is

are unknown. The residual vector is

![\[ e_{i}=\left|y_{i}-A\sin\left(2\pi kx_{i}+\theta\right)\right|.\]](../_images/math/e5f48d5aa4cadf0bc8181cf9381276494979d5dc.png)

By defining a function to compute the residuals and (selecting an

appropriate starting position), the least-squares fit routine can be

used to find the best-fit parameters  .

This is shown in the following example:

.

This is shown in the following example:

>>> from numpy import *

>>> x = arange(0,6e-2,6e-2/30)

>>> A,k,theta = 10, 1.0/3e-2, pi/6

>>> y_true = A*sin(2*pi*k*x+theta)

>>> y_meas = y_true + 2*random.randn(len(x))

>>> def residuals(p, y, x):

... A,k,theta = p

... err = y-A*sin(2*pi*k*x+theta)

... return err

>>> def peval(x, p):

... return p[0]*sin(2*pi*p[1]*x+p[2])

>>> p0 = [8, 1/2.3e-2, pi/3]

>>> print array(p0)

[ 8. 43.4783 1.0472]

>>> from scipy.optimize import leastsq

>>> plsq = leastsq(residuals, p0, args=(y_meas, x))

>>> print plsq[0]

[ 10.9437 33.3605 0.5834]

>>> print array([A, k, theta])

[ 10. 33.3333 0.5236]

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

>>> plt.plot(x,peval(x,plsq[0]),x,y_meas,'o',x,y_true)

>>> plt.title('Least-squares fit to noisy data')

>>> plt.legend(['Fit', 'Noisy', 'True'])

>>> plt.show()

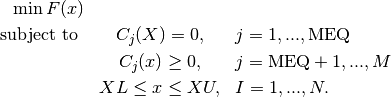

Sequential Least-square fitting with constraints (fmin_slsqp)¶

This module implements the Sequential Least SQuares Programming optimization algorithm (SLSQP).

The following script shows examples for how constraints can be specified.

"""

This script tests fmin_slsqp using Example 14.4 from Numerical Methods for

Engineers by Steven Chapra and Raymond Canale. This example maximizes the

function f(x) = 2*x0*x1 + 2*x0 - x0**2 - 2*x1**2, which has a maximum

at x0=2, x1=1.

"""

from scipy.optimize import fmin_slsqp

from numpy import array

def testfunc(x, *args):

"""

Parameters

----------

d : list

A list of two elements, where d[0] represents x and

d[1] represents y in the following equation.

args : tuple

First element of args is a multiplier for f.

Since the objective function should be maximized, and the scipy

optimizers can only minimize functions, it is nessessary to

multiply the objective function by -1 to achieve the desired

solution.

Returns

-------

res : float

The result, equal to ``2*x*y + 2*x - x**2 - 2*y**2``.

"""

try:

sign = args[0]

except:

sign = 1.0

return sign*(2*x[0]*x[1] + 2*x[0] - x[0]**2 - 2*x[1]**2)

def testfunc_deriv(x,*args):

""" This is the derivative of testfunc, returning a numpy array

representing df/dx and df/dy """

try:

sign = args[0]

except:

sign = 1.0

dfdx0 = sign*(-2*x[0] + 2*x[1] + 2)

dfdx1 = sign*(2*x[0] - 4*x[1])

return array([ dfdx0, dfdx1 ])

def test_eqcons(x,*args):

""" Lefthandside of the equality constraint """

return array([ x[0]**3-x[1] ])

def test_ieqcons(x,*args):

""" Lefthandside of inequality constraint """

return array([ x[1]-1 ])

def test_fprime_eqcons(x,*args):

""" First derivative of equality constraint """

return array([ 3.0*(x[0]**2.0), -1.0 ])

def test_fprime_ieqcons(x,*args):

""" First derivative of inequality constraint """

return array([ 0.0, 1.0 ])

from time import time

print "Unbounded optimization."

print "Derivatives of objective function approximated."

t0 = time()

result = fmin_slsqp(testfunc, [-1.0,1.0], args=(-1.0,), iprint=2, full_output=1)

print "Elapsed time:", 1000*(time()-t0), "ms"

print "Results", result, "\n\n"

print "Unbounded optimization."

print "Derivatives of objective function provided."

t0 = time()

result = fmin_slsqp(testfunc, [-1.0,1.0], fprime=testfunc_deriv, args=(-1.0,),

iprint=2, full_output=1)

print "Elapsed time:", 1000*(time()-t0), "ms"

print "Results", result, "\n\n"

print "Bound optimization (equality constraints)."

print "Constraints implemented via lambda function."

print "Derivatives of objective function approximated."

print "Derivatives of constraints approximated."

t0 = time()

result = fmin_slsqp(testfunc, [-1.0,1.0], args=(-1.0,),

eqcons=[lambda x, args: x[0]-x[1] ], iprint=2, full_output=1)

print "Elapsed time:", 1000*(time()-t0), "ms"

print "Results", result, "\n\n"

print "Bound optimization (equality constraints)."

print "Constraints implemented via lambda."

print "Derivatives of objective function provided."

print "Derivatives of constraints approximated."

t0 = time()

result = fmin_slsqp(testfunc, [-1.0,1.0], fprime=testfunc_deriv, args=(-1.0,),

eqcons=[lambda x, args: x[0]-x[1] ], iprint=2, full_output=1)

print "Elapsed time:", 1000*(time()-t0), "ms"

print "Results", result, "\n\n"

print "Bound optimization (equality and inequality constraints)."

print "Constraints implemented via lambda."

print "Derivatives of objective function provided."

print "Derivatives of constraints approximated."

t0 = time()

result = fmin_slsqp(testfunc,[-1.0,1.0], fprime=testfunc_deriv, args=(-1.0,),

eqcons=[lambda x, args: x[0]-x[1] ],

ieqcons=[lambda x, args: x[0]-.5], iprint=2, full_output=1)

print "Elapsed time:", 1000*(time()-t0), "ms"

print "Results", result, "\n\n"

print "Bound optimization (equality and inequality constraints)."

print "Constraints implemented via function."

print "Derivatives of objective function provided."

print "Derivatives of constraints approximated."

t0 = time()

result = fmin_slsqp(testfunc, [-1.0,1.0], fprime=testfunc_deriv, args=(-1.0,),

f_eqcons=test_eqcons, f_ieqcons=test_ieqcons,

iprint=2, full_output=1)

print "Elapsed time:", 1000*(time()-t0), "ms"

print "Results", result, "\n\n"

print "Bound optimization (equality and inequality constraints)."

print "Constraints implemented via function."

print "All derivatives provided."

t0 = time()

result = fmin_slsqp(testfunc,[-1.0,1.0], fprime=testfunc_deriv, args=(-1.0,),

f_eqcons=test_eqcons, fprime_eqcons=test_fprime_eqcons,

f_ieqcons=test_ieqcons, fprime_ieqcons=test_fprime_ieqcons,

iprint=2, full_output=1)

print "Elapsed time:", 1000*(time()-t0), "ms"

print "Results", result, "\n\n"

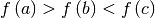

Scalar function minimizers¶

Often only the minimum of a scalar function is needed (a scalar function is one that takes a scalar as input and returns a scalar output). In these circumstances, other optimization techniques have been developed that can work faster.

Unconstrained minimization (brent)¶

There are actually two methods that can be used to minimize a scalar

function (brent and golden), but golden is

included only for academic purposes and should rarely be used. The

brent method uses Brent’s algorithm for locating a minimum. Optimally

a bracket should be given which contains the minimum desired. A

bracket is a triple  such that

such that

and

and

. If this is not given, then alternatively two starting

points can be chosen and a bracket will be found from these points

using a simple marching algorithm. If these two starting points are

not provided 0 and 1 will be used (this may not be the right choice

for your function and result in an unexpected minimum being returned).

. If this is not given, then alternatively two starting

points can be chosen and a bracket will be found from these points

using a simple marching algorithm. If these two starting points are

not provided 0 and 1 will be used (this may not be the right choice

for your function and result in an unexpected minimum being returned).

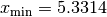

Bounded minimization (fminbound)¶

Thus far all of the minimization routines described have been unconstrained minimization routines. Very often, however, there are constraints that can be placed on the solution space before minimization occurs. The fminbound function is an example of a constrained minimization procedure that provides a rudimentary interval constraint for scalar functions. The interval constraint allows the minimization to occur only between two fixed endpoints.

For example, to find the minimum of  near

near  , fminbound can be called using the interval

, fminbound can be called using the interval ![\left[4,7\right]](../_images/math/fb3f8cdf1cd70a262c58ad6a68d660a3ebdf0017.png) as a constraint. The result is

as a constraint. The result is  :

:

>>> from scipy.special import j1

>>> from scipy.optimize import fminbound

>>> xmin = fminbound(j1, 4, 7)

>>> print xmin

5.33144184241

Root finding¶

Sets of equations¶

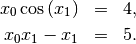

To find the roots of a polynomial, the command roots is useful. To find a root of a set of non-linear equations, the command fsolve is needed. For example, the following example finds the roots of the single-variable transcendental equation

![\[ x+2\cos\left(x\right)=0,\]](../_images/math/7f83e112da2ff7a423f7ffcd84d834c55a699237.png)

and the set of non-linear equations

The results are  and

and  .

.

>>> def func(x):

... return x + 2*cos(x)

>>> def func2(x):

... out = [x[0]*cos(x[1]) - 4]

... out.append(x[1]*x[0] - x[1] - 5)

... return out

>>> from scipy.optimize import fsolve

>>> x0 = fsolve(func, 0.3)

>>> print x0

-1.02986652932

>>> x02 = fsolve(func2, [1, 1])

>>> print x02

[ 6.50409711 0.90841421]

Scalar function root finding¶

If one has a single-variable equation, there are four different root finder algorithms that can be tried. Each of these root finding algorithms requires the endpoints of an interval where a root is suspected (because the function changes signs). In general brentq is the best choice, but the other methods may be useful in certain circumstances or for academic purposes.

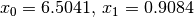

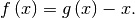

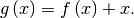

Fixed-point solving¶

A problem closely related to finding the zeros of a function is the

problem of finding a fixed-point of a function. A fixed point of a

function is the point at which evaluation of the function returns the

point:  Clearly the fixed point of

Clearly the fixed point of  is the root of

is the root of  Equivalently, the root of

Equivalently, the root of  is the fixed_point of

is the fixed_point of

The routine

fixed_point provides a simple iterative method using Aitkens

sequence acceleration to estimate the fixed point of

The routine

fixed_point provides a simple iterative method using Aitkens

sequence acceleration to estimate the fixed point of  given a

starting point.

given a

starting point.

Root finding: Large problems¶

The fsolve function cannot deal with a very large number of variables (N), as it needs to calculate and invert a dense N x N Jacobian matrix on every Newton step. This becomes rather inefficent when N grows.

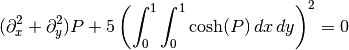

Consider for instance the following problem: we need to solve the

following integrodifferential equation on the square

![[0,1]\times[0,1]](../_images/math/a6aa56acfcb95ab5be4a1c4210c59219c425167b.png) :

:

with the boundary condition  on the upper edge and

on the upper edge and

elsewhere on the boundary of the square. This can be done

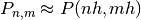

by approximating the continuous function P by its values on a grid,

elsewhere on the boundary of the square. This can be done

by approximating the continuous function P by its values on a grid,

, with a small grid spacing

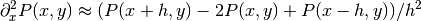

h. The derivatives and integrals can then be approximated; for

instance

, with a small grid spacing

h. The derivatives and integrals can then be approximated; for

instance  . The problem is then equivalent to finding the root of

some function residual(P), where P is a vector of length

. The problem is then equivalent to finding the root of

some function residual(P), where P is a vector of length

.

.

Now, because  can be large, fsolve will take a

long time to solve this problem. The solution can however be found

using one of the large-scale solvers in scipy.optimize, for

example newton_krylov, broyden2, or

anderson. These use what is known as the inexact Newton method,

which instead of computing the Jacobian matrix exactly, forms an

approximation for it.

can be large, fsolve will take a

long time to solve this problem. The solution can however be found

using one of the large-scale solvers in scipy.optimize, for

example newton_krylov, broyden2, or

anderson. These use what is known as the inexact Newton method,

which instead of computing the Jacobian matrix exactly, forms an

approximation for it.

The problem we have can now be solved as follows:

import numpy as np

from scipy.optimize import newton_krylov

from numpy import cosh, zeros_like, mgrid, zeros

# parameters

nx, ny = 75, 75

hx, hy = 1./(nx-1), 1./(ny-1)

P_left, P_right = 0, 0

P_top, P_bottom = 1, 0

def residual(P):

d2x = zeros_like(P)

d2y = zeros_like(P)

d2x[1:-1] = (P[2:] - 2*P[1:-1] + P[:-2]) / hx/hx

d2x[0] = (P[1] - 2*P[0] + P_left)/hx/hx

d2x[-1] = (P_right - 2*P[-1] + P[-2])/hx/hx

d2y[:,1:-1] = (P[:,2:] - 2*P[:,1:-1] + P[:,:-2])/hy/hy

d2y[:,0] = (P[:,1] - 2*P[:,0] + P_bottom)/hy/hy

d2y[:,-1] = (P_top - 2*P[:,-1] + P[:,-2])/hy/hy

return d2x + d2y + 5*cosh(P).mean()**2

# solve

guess = zeros((nx, ny), float)

sol = newton_krylov(residual, guess, verbose=1)

#sol = broyden2(residual, guess, max_rank=50, verbose=1)

#sol = anderson(residual, guess, M=10, verbose=1)

print 'Residual', abs(residual(sol)).max()

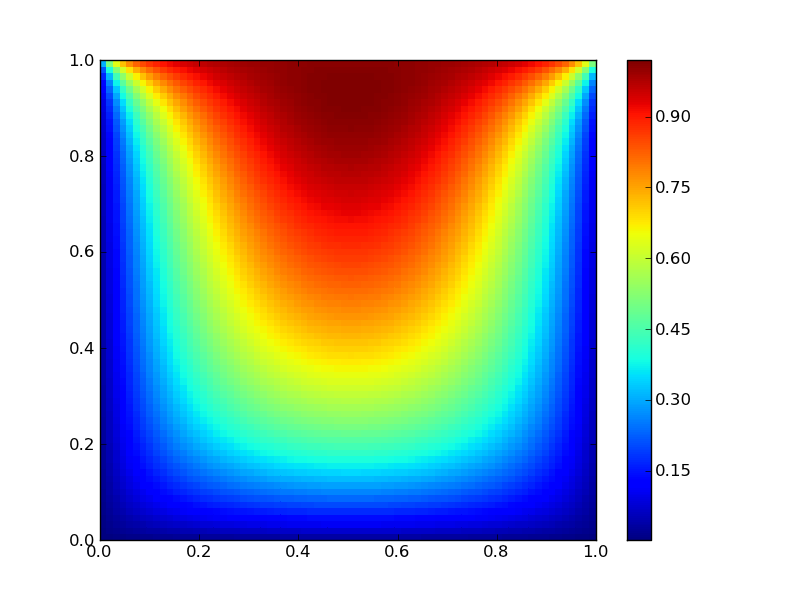

# visualize

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x, y = mgrid[0:1:(nx*1j), 0:1:(ny*1j)]

plt.pcolor(x, y, sol)

plt.colorbar()

plt.show()

Still too slow? Preconditioning.¶

When looking for the zero of the functions  ,

i = 1, 2, ..., N, the newton_krylov solver spends most of its

time inverting the Jacobian matrix,

,

i = 1, 2, ..., N, the newton_krylov solver spends most of its

time inverting the Jacobian matrix,

If you have an approximation for the inverse matrix

, you can use it for preconditioning the

linear inversion problem. The idea is that instead of solving

, you can use it for preconditioning the

linear inversion problem. The idea is that instead of solving

one solves

one solves  : since

matrix

: since

matrix  is “closer” to the identity matrix than

is “closer” to the identity matrix than  is, the equation should be easier for the Krylov method to deal with.

is, the equation should be easier for the Krylov method to deal with.

The matrix M can be passed to newton_krylov as the inner_M parameter. It can be a (sparse) matrix or a scipy.sparse.linalg.LinearOperator instance.

For the problem in the previous section, we note that the function to

solve consists of two parts: the first one is application of the

Laplace operator, ![[\partial_x^2 + \partial_y^2] P](../_images/math/fd7e27145d5874102e803d1448af9b49f35865f8.png) , and the second

is the integral. We can actually easily compute the Jacobian corresponding

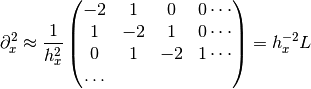

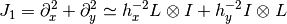

to the Laplace operator part: we know that in one dimension

, and the second

is the integral. We can actually easily compute the Jacobian corresponding

to the Laplace operator part: we know that in one dimension

so that the whole 2-D operator is represented by

The matrix  of the Jacobian corresponding to the integral

is more difficult to calculate, and since all of it entries are

nonzero, it will be difficult to invert.

of the Jacobian corresponding to the integral

is more difficult to calculate, and since all of it entries are

nonzero, it will be difficult to invert.  on the other hand

is a relatively simple matrix, and can be inverted by

scipy.sparse.linalg.splu (or the inverse can be approximated by

scipy.sparse.linalg.spilu). So we are content to take

on the other hand

is a relatively simple matrix, and can be inverted by

scipy.sparse.linalg.splu (or the inverse can be approximated by

scipy.sparse.linalg.spilu). So we are content to take

and hope for the best.

and hope for the best.

In the example below, we use the preconditioner  .

.

import numpy as np

from scipy.optimize import newton_krylov

from scipy.sparse import spdiags, spkron

from scipy.sparse.linalg import spilu, LinearOperator

from numpy import cosh, zeros_like, mgrid, zeros, eye

# parameters

nx, ny = 75, 75

hx, hy = 1./(nx-1), 1./(ny-1)

P_left, P_right = 0, 0

P_top, P_bottom = 1, 0

def get_preconditioner():

"""Compute the preconditioner M"""

diags_x = zeros((3, nx))

diags_x[0,:] = 1/hx/hx

diags_x[1,:] = -2/hx/hx

diags_x[2,:] = 1/hx/hx

Lx = spdiags(diags_x, [-1,0,1], nx, nx)

diags_y = zeros((3, ny))

diags_y[0,:] = 1/hy/hy

diags_y[1,:] = -2/hy/hy

diags_y[2,:] = 1/hy/hy

Ly = spdiags(diags_y, [-1,0,1], ny, ny)

J1 = spkron(Lx, eye(ny)) + spkron(eye(nx), Ly)

# Now we have the matrix `J_1`. We need to find its inverse `M` --

# however, since an approximate inverse is enough, we can use

# the *incomplete LU* decomposition

J1_ilu = spilu(J1)

# This returns an object with a method .solve() that evaluates

# the corresponding matrix-vector product. We need to wrap it into

# a LinearOperator before it can be passed to the Krylov methods:

M = LinearOperator(shape=(nx*ny, nx*ny), matvec=J1_ilu.solve)

return M

def solve(preconditioning=True):

"""Compute the solution"""

count = [0]

def residual(P):

count[0] += 1

d2x = zeros_like(P)

d2y = zeros_like(P)

d2x[1:-1] = (P[2:] - 2*P[1:-1] + P[:-2])/hx/hx

d2x[0] = (P[1] - 2*P[0] + P_left)/hx/hx

d2x[-1] = (P_right - 2*P[-1] + P[-2])/hx/hx

d2y[:,1:-1] = (P[:,2:] - 2*P[:,1:-1] + P[:,:-2])/hy/hy

d2y[:,0] = (P[:,1] - 2*P[:,0] + P_bottom)/hy/hy

d2y[:,-1] = (P_top - 2*P[:,-1] + P[:,-2])/hy/hy

return d2x + d2y + 5*cosh(P).mean()**2

# preconditioner

if preconditioning:

M = get_preconditioner()

else:

M = None

# solve

guess = zeros((nx, ny), float)

sol = newton_krylov(residual, guess, verbose=1, inner_M=M)

print 'Residual', abs(residual(sol)).max()

print 'Evaluations', count[0]

return sol

def main():

sol = solve(preconditioning=True)

# visualize

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x, y = mgrid[0:1:(nx*1j), 0:1:(ny*1j)]

plt.clf()

plt.pcolor(x, y, sol)

plt.clim(0, 1)

plt.colorbar()

plt.show()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Resulting run, first without preconditioning:

0: |F(x)| = 803.614; step 1; tol 0.000257947

1: |F(x)| = 345.912; step 1; tol 0.166755

2: |F(x)| = 139.159; step 1; tol 0.145657

3: |F(x)| = 27.3682; step 1; tol 0.0348109

4: |F(x)| = 1.03303; step 1; tol 0.00128227

5: |F(x)| = 0.0406634; step 1; tol 0.00139451

6: |F(x)| = 0.00344341; step 1; tol 0.00645373

7: |F(x)| = 0.000153671; step 1; tol 0.00179246

8: |F(x)| = 6.7424e-06; step 1; tol 0.00173256

Residual 3.57078908664e-07

Evaluations 317

and then with preconditioning:

0: |F(x)| = 136.993; step 1; tol 7.49599e-06

1: |F(x)| = 4.80983; step 1; tol 0.00110945

2: |F(x)| = 0.195942; step 1; tol 0.00149362

3: |F(x)| = 0.000563597; step 1; tol 7.44604e-06

4: |F(x)| = 1.00698e-09; step 1; tol 2.87308e-12

Residual 9.29603061195e-11

Evaluations 77

Using a preconditioner reduced the number of evaluations of the residual function by a factor of 4. For problems where the residual is expensive to compute, good preconditioning can be crucial — it can even decide whether the problem is solvable in practice or not.

Preconditioning is an art, science, and industry. Here, we were lucky in making a simple choice that worked reasonably well, but there is a lot more depth to this topic than is shown here.

References

Some further reading and related software:

| [KK] | D.A. Knoll and D.E. Keyes, “Jacobian-free Newton-Krylov methods”, J. Comp. Phys. 193, 357 (2003). |

| [PP] | PETSc http://www.mcs.anl.gov/petsc/ and its Python bindings http://code.google.com/p/petsc4py/ |

| [AMG] | PyAMG (algebraic multigrid preconditioners/solvers) http://code.google.com/p/pyamg/ |