Special functions (scipy.special)¶

The main feature of the scipy.special package is the definition of

numerous special functions of mathematical physics. Available

functions include airy, elliptic, bessel, gamma, beta, hypergeometric,

parabolic cylinder, mathieu, spheroidal wave, struve, and

kelvin. There are also some low-level stats functions that are not

intended for general use as an easier interface to these functions is

provided by the stats module. Most of these functions can take

array arguments and return array results following the same

broadcasting rules as other math functions in Numerical Python. Many

of these functions also accept complex numbers as input. For a

complete list of the available functions with a one-line description

type >>> help(special). Each function also has its own

documentation accessible using help. If you don’t see a function you

need, consider writing it and contributing it to the library. You can

write the function in either C, Fortran, or Python. Look in the source

code of the library for examples of each of these kinds of functions.

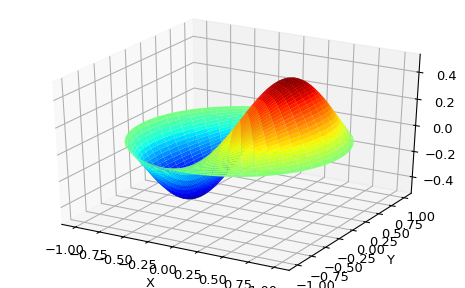

Bessel functions of real order(jn, jn_zeros)¶

Bessel functions are a family of solutions to Bessel’s differential equation with real or complex order alpha:

Among other uses, these functions arise in wave propagation problems such as the vibrational modes of a thin drum head. Here is an example of a circular drum head anchored at the edge:

>>> from scipy import special

>>> def drumhead_height(n, k, distance, angle, t):

... kth_zero = special.jn_zeros(n, k)[-1]

... return np.cos(t) * np.cos(n*angle) * special.jn(n, distance*kth_zero)

>>> theta = np.r_[0:2*np.pi:50j]

>>> radius = np.r_[0:1:50j]

>>> x = np.array([r * np.cos(theta) for r in radius])

>>> y = np.array([r * np.sin(theta) for r in radius])

>>> z = np.array([drumhead_height(1, 1, r, theta, 0.5) for r in radius])

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

>>> from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

>>> from matplotlib import cm

>>> fig = plt.figure()

>>> ax = Axes3D(fig)

>>> ax.plot_surface(x, y, z, rstride=1, cstride=1, cmap=cm.jet)

>>> ax.set_xlabel('X')

>>> ax.set_ylabel('Y')

>>> ax.set_zlabel('Z')

>>> plt.show()

Cython Bindings for Special Functions (scipy.special.cython_special)¶

Scipy also offers Cython bindings for scalar, typed versions of many of the functions in special. The following Cython code gives a simple example of how to use these functions:

cimport scipy.special.cython_special as csc

cdef:

double x = 1

double complex z = 1 + 1j

double si, ci, rgam

double complex cgam

rgam = csc.gamma(x)

print(rgam)

cgam = csc.gamma(z)

print(cgam)

csc.sici(x, &si, &ci)

print(si, ci)

(See the Cython documentation for help with compiling Cython.) In

the example the function csc.gamma works essentially like its

ufunc counterpart gamma, though it takes C types as arguments

instead of NumPy arrays. Note in particular that the function is

overloaded to support real and complex arguments; the correct variant

is selected at compile time. The function csc.sici works slightly

differently from sici; for the ufunc we could write ai, bi =

sici(x) whereas in the Cython version multiple return values are

passed as pointers. It might help to think of this as analogous to

calling a ufunc with an output array: sici(x, out=(si, ci)).

There are two potential advantages to using the Cython bindings:

They avoid Python function overhead

They do not require the Python Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)

The following sections discuss how to use these advantages to potentially speed up your code, though of course one should always profile the code first to make sure putting in the extra effort will be worth it.

Avoiding Python Function Overhead¶

For the ufuncs in special, Python function overhead is avoided by vectorizing, that is, by passing an array to the function. Typically this approach works quite well, but sometimes it is more convenient to call a special function on scalar inputs inside a loop, for example when implementing your own ufunc. In this case the Python function overhead can become significant. Consider the following example:

import scipy.special as sc

cimport scipy.special.cython_special as csc

def python_tight_loop():

cdef:

int n

double x = 1

for n in range(100):

sc.jv(n, x)

def cython_tight_loop():

cdef:

int n

double x = 1

for n in range(100):

csc.jv(n, x)

On one computer python_tight_loop took about 131 microseconds to

run and cython_tight_loop took about 18.2 microseconds to

run. Obviously this example is contrived: one could just call

special.jv(np.arange(100), 1) and get results just as fast as in

cython_tight_loop. The point is that if Python function overhead

becomes significant in your code then the Cython bindings might be

useful.

Releasing the GIL¶

One often needs to evaluate a special function at many points, and

typically the evaluations are trivially parallelizable. Since the

Cython bindings do not require the GIL, it is easy to run them in

parallel using Cython’s prange function. For example, suppose that

we wanted to compute the fundamental solution to the Helmholtz

equation:

where \(k\) is the wavenumber and \(\delta\) is the Dirac delta function. It is known that in two dimensions the unique (radiating) solution is

where \(H_0^{(1)}\) is the Hankel function of the first kind,

i.e. the function hankel1. The following example shows how we could

compute this function in parallel:

from libc.math cimport fabs

cimport cython

from cython.parallel cimport prange

import numpy as np

import scipy.special as sc

cimport scipy.special.cython_special as csc

def serial_G(k, x, y):

return 0.25j*sc.hankel1(0, k*np.abs(x - y))

@cython.boundscheck(False)

@cython.wraparound(False)

cdef void _parallel_G(double k, double[:,:] x, double[:,:] y,

double complex[:,:] out) nogil:

cdef int i, j

for i in prange(x.shape[0]):

for j in range(y.shape[0]):

out[i,j] = 0.25j*csc.hankel1(0, k*fabs(x[i,j] - y[i,j]))

def parallel_G(k, x, y):

out = np.empty_like(x, dtype='complex128')

_parallel_G(k, x, y, out)

return out

(For help with compiling parallel code in Cython see here.) If the

above Cython code is in a file test.pyx, then we can write an

informal benchmark which compares the parallel and serial versions of

the function:

import timeit

import numpy as np

from test import serial_G, parallel_G

def main():

k = 1

x, y = np.linspace(-100, 100, 1000), np.linspace(-100, 100, 1000)

x, y = np.meshgrid(x, y)

def serial():

serial_G(k, x, y)

def parallel():

parallel_G(k, x, y)

time_serial = timeit.timeit(serial, number=3)

time_parallel = timeit.timeit(parallel, number=3)

print("Serial method took {:.3} seconds".format(time_serial))

print("Parallel method took {:.3} seconds".format(time_parallel))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

On one quad-core computer the serial method took 1.29 seconds and the parallel method took 0.29 seconds.

Functions not in scipy.special¶

Some functions are not included in special because they are

straightforward to implement with existing functions in NumPy and

SciPy. To prevent reinventing the wheel, this section provides

implementations of several such functions which hopefully illustrate

how to handle similar functions. In all examples NumPy is imported as

np and special is imported as sc.

def binary_entropy(x):

return -(sc.xlogy(x, x) + sc.xlog1py(1 - x, -x))/np.log(2)

A rectangular step function on [0, 1]:

def step(x):

return 0.5*(np.sign(x) + np.sign(1 - x))

Translating and scaling can be used to get an arbitrary step function.

The ramp function:

def ramp(x):

return np.maximum(0, x)